April 20, 2020. As we stay in social isolation during the Coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic, many people are wondering how we will react once the restrictions are lifted, how they will be lifted, and when they will be lifted. At the moment there are no clear answers. But there are examples in the past about how people reacted when major events came to an end. One of these was the reaction of WW1 soldiers when they learned that the war would end on the 11th hour of the 11th month in 1918. Some didn’t believe it would happen, others wondered why wait when a ceasefire was already in the works. Some thought to reduce the loss of life by not actively pursuing the soon to be ex-enemy, while others strove to aggressively take out as many enemies out as possible. George Lawrence PRICE, the Canadian soldier who was shot by a German sniper and died two minutes before the 11 am ceasefire comes to mind as an example of the latter. (See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Lawrence_Price)

Harold Keith HOWATT, of Augustine Cove, was in the 8th Canadian Siege Battery during WW1 and survived the war. With this year’s pandemic in mind, we looked through his writings to see if there was any mention of what later became known as the Spanish flu among the troops. To our surprise, only one mention was made of flu, and it had nothing to do with soldiers! On October 29, 1918 he wrote that “….I received three letters from PEI and in one of them was the news that Morley Newsome had died of influenza. It was quite a blow to me, we had always been such good friends….” (Newsome, the son of Samuel Newsome and Charlotte Dawson, died on October 8, 1918, and is buried in Charlottetown.)

Next we wondered what he wrote once the news of an upcoming ceasefire was announced. The first mention is of a rumour on November 5, 1918, while he was in Hérin, France, not that far from the Belgian border. “…The Allied Army is going strong all along the line, the Belgians are reported to be in Ghent, the Americans have captured Sedan, and the French are going strong. There are rumours of an armistice…”

Orange star is the approximate location of Hérin, France where Howatt was located in early November. Brown arrow is the location of Sedan, Belgium. (Map source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hundred_Days_Offensive)

On November 6, 1918, he wrote that “…Peace rumours growing stronger. It is reported that Mons is captured, also that the Germans have asked the Allied Command if they will receive a peace delegation…” Mons is in Belgium.

The next day, November 7, he recorded that it was “….officially reported that Turkey and Austria have unconditionally surrendered, that the Allied Fleet is in the Black Sea, and that Austria has to allow the Allies to march through their territory to attack Germany from the south…”

On November 8, he sounds a hopeful note. “…It is official that Germany is sending a peace delegation across the lines. No one knows where the Germans are in front of here, somewhere beyond Mons. There is great expectation of peace….”

On November 9, he writes about going into the nearby town of Denain for a concert and later to visit a canteen where he met Canadians who recently arrived from England. “… There were a great number of Canadians in Denain today, two or three thousand reinforcements who have just come over from Blighty. The rumour tonight is that the Allies have given Germany until Monday at 11:00 hours to agree to the terms of the armistice….” All these rumours in the days before social media indicate the keen interest in what was happening!

Hérin is circled in purple. Denain is circled in orange. (Source: Google map for area around Cambrai, France.)

On November 10, Howatt’s unit was woken up at 5 am and told they would be on the move to Boussu, Belgium, a small town 10 kms west of Mons. Then nothing happened all morning! Hurry up and wait? Finally, after dinner, Howatt was part of an advance party that left in a truck with “…several signallers, two cooks, and Lutly and I…”

Howatt’s advance party travelled through Valenciennes to Boussu. (Map source: Google)

When they arrived in Boussu, Howatt recorded that “…There are a large number of civilians in the town, and there was great excitement among the civilians, the band started to play, and the civilians flocked around, and started to dance, sing, and shout ‘La guerre est fini’. The general impression seems to be that the war is about over…..”

The first entry for Monday, November 11, 1918 was in quotes and underlined. “Hostilities have ceased.” Howatt then gave an account of the reaction. “….At eleven o’clock this morning fighting ceased, the Germans have evidently accepted the terms of the armistice. There was not much excitement today, the fellows hardly believe that it is true. There is just a quiet undertone of gladness…”

With fighting over, the rest of Howatt’s unit came to Boussu and they were billeted in a chateau built in 1539 and belonging to the Marquisse de Charbonne, a Parisian who used the chateau as a summer home. Howatt mentions that the chateau had been “…used by Fritz as billets. When we got over there to hold the billets we found about twenty Belgian girls here cleaning out the place. It was in an awful mess….. We certainly had a circus here this morning with those girls, they would work for a while, then they would have a dance. I laughed more than I have for ages….”

The end of fighting didn’t mean that soldiers were free to leave. On November 12, Howatt reports that “…Gun crews went down to clean the guns and signallers and B.C.A.s to clean their stores…” (B.C.A. is an acronym for Battery Commander Assistant, the position held by Howatt.)

On November 13, Howatt mentions more rumours going through his unit. “...There are all sorts of rumours going around today, some say that we are going up into Germany, others say we are going right back to Canada. I wouldn’t mind going into Germany at all….” Not long afterwards, Howatt did go to Germany as part of the Army of Occupation.

We think of major events as having a beginning and an end. They do, but the timing is staggered and never crystal clear. Not only are there rumours, but there is a time lag when people begin to believe that what they have been told is true. It must have been an enormous shock, mixed with relief, to learn that fighting was over, and then came the uncertainty while waiting to hear what would happen next. This is a lesson for us with the pandemic.

After returning home, Howatt married Louise Wright, and died on October 15, 1985, aged 93. Does anyone have a photo of Harold Howatt? If so, please let Pieter know. You can email him at dariadv@yahoo.ca or comment on the blog.

© Daria Valkenburg

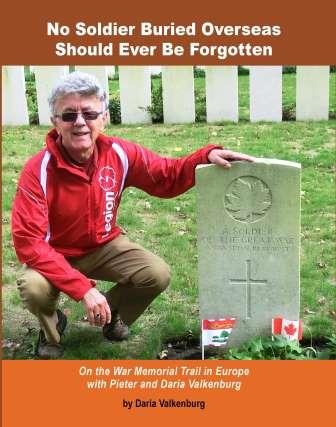

4 countries, 6 weeks, 7,000 km – an unforgettable war memorial journey in Europe….

4 countries, 6 weeks, 7,000 km – an unforgettable war memorial journey in Europe….