April 29, 2020. In an earlier posting, the observations made by Harold Keith HOWATT of Augustine Cove towards the end of WW1 were recorded. (See One Soldier Records His Observations During The Last Few Days Of World War I) Howatt was in the 8th Canadian Siege Battery during WW1 and came home after the war.

On October 30, 1918, as Howatt’s unit travelled towards Belgium from France in the last days of the war, the Brigade was inspected by Lt-General Sir Arthur Currie. (Harold Howatt collection. Photo from ‘Purely Personal’ issue of November 30, 1918.)

After the official hostilities ended on November 11, Howatt was in Belgium with his unit, and hoped he could go to Germany with the Army of Occupation. He got his wish.

On November 17, 1918, Howatt’s unit was informed it would be attached to the 2nd Brigade, the only Canadian Heavy Artillery Brigade going to Germany.

Before the march into Germany, however, Howatt wrote, on November 19, 1918, how happy he was to have a real bath… “...Wonderful to relate, we had a bath parade to the bath at one of the mines. It was a rather long walk but a great bath when we got there, a shower bath with lots of warm water…”

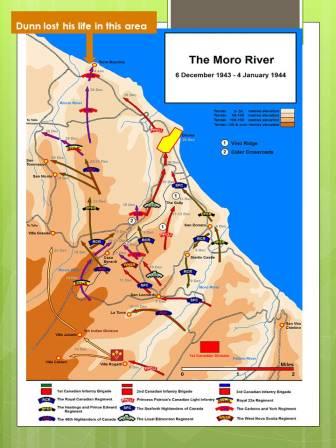

Route from Mons, Belgium to Mehlem (near Bonn), Germany taken by Howatt’s unit. (Map courtesy of http://www.duckduckgo.com)

On November 20, the unit was on the move. “…Breakfast at 5 o’clock this morning, then we fell in at 6:30 and marched up to the square. Here we formed up and started for Germany, the lorries ahead, then the signallers and B.C.A.s, then the guns with the gun crews walking behind….” (B.C.A. is an acronym for Battery Commander Assistant, the position held by Howatt.) “...We stopped at a town called Jemappes, about four kms west of Mons. We were billeted in a big factory, away up in the top story...” The unit stayed there for a week.

On November 28, 1918, Howatt and his unit were on their way again. “…Up this morning at 5:30, had two cups of coffee, then breakfast, and away. We travelled in the lorries through town after town. Had great fun waving our hands to all the pretty girls as we passed…” Pretty girls weren’t all that caught Howatt’s interest. “…We stopped in one town for a few minutes and we were talking to a Canadian infantry corporal. His company was guarding trainloads of munitions left by the Germans. They had big munitions works in the town, and there were over 300 cars of shells and high explosives in the railway yards…” Howatt didn’t identify this town, but mentioned that they stopped overnight in Ligny, and he was billeted in a farmhouse with a Belgian family.

The next day, November 29, Howatt continued his account. “…Left Ligny this morning at about eight o’clock and arrived here in Namur about twelve. All along the road are abandoned German lorries, tractors, and motorcars. They must have left hundreds and hundreds behind them. I don’t know whether these cars have broken down or whether the petrol gave out. I saw one yard full of lorries….”

Postcard showing the citadel in Namur. (Harold Howatt collection.)

The unit stopped in Namur for a rest break, giving Howatt time to explore the town. “…Namur is quite a place. The forts are on a high cliff or hill behind the town. The town has been badly smashed up in some places….”

On December 1, the unit was moving ahead again. “…We started about seven. The road ran along the bank of the Meuse, and on the other side are enormous cliffs towering high in the air…..” While Howatt, as part of the advance party, arrived in Huy around noon to secure accommodations “….the guns did not get in until nearly dark. Just as we were waiting around for supper Mr. Goodwin came around and said that the B.C.A.s and signallers had to clear the mud off the wheels…” Howatt, along with a small group, cleared off one gun, but noted that a number of men disappeared, rather than going out in the dark to tackle this task!

The next day, rather than continuing on, the unit was put to work cleaning the guns. On December 4, the unit moved further along to Hamoir, where they stopped for another few days. On December 8, the unit travelled as far as Petit-Thier “…only 3 kms from the border. It is a very small place…”

On December 9, Howatt recorded that “…At last we are where we have been trying to get for over four years. ‘In Germany’ This morning, at about eight o’clock we crossed the frontier, the first Canadian Siege Battery to enter Germany….”

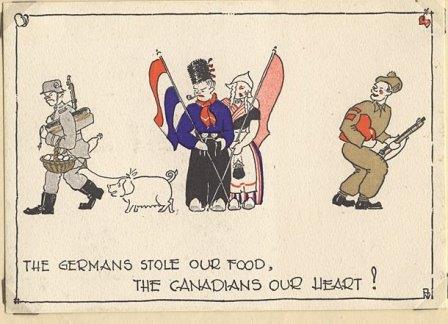

He noted that the mood in Germany was not the same as in Belgium. “…About the only difference we noted on crossing the frontier was the absence of flags and any demonstrations on the part of the people. They still came out when we passed and just looked at us without a word or smile. One or two we met on the road saluted us. The people do not seem to fear us, in fact I think they welcome us, hoping the presence of the troops will restore order, and result in a more even distribution of food. The country we passed through today was desolate….” That night they stopped in a small village, Mirfeld, where Howatt was “…billeted in a schoolroom...”

On December 10, while trying to find a place to stay in Büllingen, the unit ran into opposition. “…At first they were going to put us in the station house, but the old station master kicked about it, saying he had a telegram from a conference in Aix-la-Chapelle saying that station houses were not to be used for billeting troops...” The Canadians found other accommodation.

By December 12, they had reached Cologne, and the next day, December 13, “….the Canadian troops marched across the Rhine, reviewed as they crossed the bridge by General Plumer and General Currie. It was an inspiring sight to see the Canadians cross to the east bank of the Rhine….. The people here do not seem to be very hostile, in fact many are quite friendly but it must have been a bitter pill for these proud Prussians to swallow to have to witness the occupation of their city by the hated Canadians….”

On December 16, the unit travelled to its final destination in Germany. “….We started about 1:30 pm for Bonn or somewhere near. We passed through Bonn…. and arrived about dusk in a little town called Mehlem. We are billeted in an old theatre….”

The 2nd Canadian Brigade stayed in Mehlem until January 28, 1919, when the Canadian Army of Occupation was relieved by the British 84th Brigade Royal Garrison Artillery. Canadian troops moved back to Belgium and then onwards towards demobilization and home. Howatt was discharged on May 18, 1919.

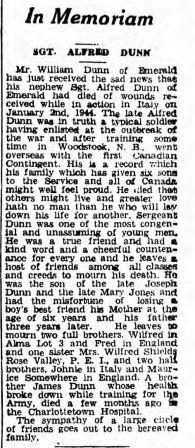

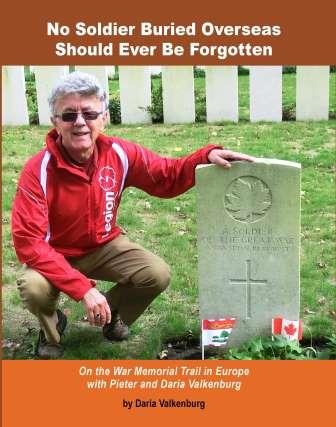

There is an Island link between the Canadian Brigade, which Howatt was part of, and the British Brigade! One of the members of the British Army of Occupation was Lt. Henry “Harry” Warburton STEWART, one of the names listed on the Cenotaph outside the Borden-Carleton Legion. Stewart died in hospital while in Germany and is buried in Cologne. (For an account of our visit to the cemetery and his story, see On the War Memorial Trail ….. In Cologne)

Henry “Harry” Warburton Stewart. (Photo courtesy B. Stewart family collection)

At the time we visited Cologne we did not have access to the war diaries for Stewart’s unit. Thanks to the coronavirus pandemic we got a lucky break. The National Archives in the United Kingdom has offered free access to its digitized records while the Archives are closed to the public. Pieter was able to get the war diaries, so we now have confirmation why Stewart was in Germany.

His unit, the 77th Siege Battery Royal Garrison Artillery, became part of the 84th Brigade Royal Garrison Artillery, sent to relieve the Canadians. According to the war diary, on January 29, 1919 “….a party of the 77th Siege Battery arrived in Namur…” Unlike Howatt’s unit, which travelled by road, this unit “…. travelled to Mehlem by train...” No mention is made of where in Mehlem the 77th Siege Battery was billeted. Stewart must have fallen ill shortly after arriving in Mehlem as he ended up in hospital in nearby Bonn and died on February 11.

Unfortunately, as yet, we have not yet found a photo of Harold Howatt. As well, the service file for Henry Warburton Stewart has not yet been digitized by the National Archives and is not available online. Can you help? If so, please let Pieter know. You can email him at dariadv@yahoo.ca or comment on the blog.

© Daria Valkenburg

4 countries, 6 weeks, 7,000 km – an unforgettable war memorial journey in Europe….

4 countries, 6 weeks, 7,000 km – an unforgettable war memorial journey in Europe….