January 21, 2026. For the past several years, in the week before Remembrance Day, the Winnipeg Free Press newspaper features a soldier on one of the photo search lists that Pieter gets from the Canadian War Cemeteries in The Netherlands. For the November 2025 feature, journalist Kevin Rollason asked if Pieter had a soldier on his list from Winnipeg, my home town.

Pieter said yes, and asked if Kevin would feature a soldier, buried in the Canadian War Cemetery in Bergen Op Zoom, The Netherlands, who overcame a traumatic childhood and was recognized for ‘gallant and distinguished service’ during the Dieppe Raid (Operation Jubilee) on August 19, 1942, before losing his life on October 27, 1944, aged 22, during the Battle of the Scheldt. The search for a photo of the soldier was still active when Kevin’s story ‘Searching For A Hero’ was published on November 10, 2025. (See Searching for a hero by Kevin Rollason)

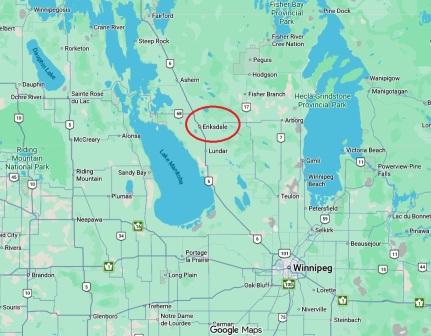

Charles ‘Gordon’ ERICKSON was born July 27, 1922 in Winnipeg, Manitoba, the son of Frank and Helen (Ellen) Gordon (nee Grant) Erickson. According to their marriage record, Frank was born in USA, and Helen in Scotland. Gordon was the middle child, with an older sister, Hazel Francis, and a younger sister, Barbara ‘Nancy’.

….Gordon and his sister Nancy ended up in the care of the Children’s Aid Society…

It’s unclear exactly what happened, but before Gordon turned 5, the family had fractured. A Free Press Evening Bulletin notice from July 5, 1927 stated that Gordon and Nancy would be put into care of the Children’s Aid Society as of July 27, 1927. The two children had been adopted by two different families. Unfortunately, both adoptions failed, putting them into care.

In the end, the two were separated from each other and didn’t reconnect until both were in service during WWII. The fate of their older sister Hazel was unknown to them.

Shortly after the Winnipeg Free Press article was published, Nancy’s son, Gordon Barker, contacted Pieter. He explained that Frank “….worked on railroad and abandoned his wife and children, and it was believed that he returned to the USA. Helen travelled to Minneapolis to look for him, had a nervous breakdown, and ended up in a mental institution, where she is thought to have died, circa 1966….”

…. Gordon lied about his age upon enlistment…

Life was not easy for Gordon during his childhood. When he enlisted on January 2, 1940 with the No. 5 General Hospital, Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps (RCAMC), Canadian Active Service Force (CASF), he wrote that he was born in 1918. This was later changed to 1919, which was still incorrect as he was born in 1922.

His next of kin was originally listed as his father, but this was then changed to his Children’s Aid Society Guardian, Joseph Dumas. When asked if he had ever worked before enlistment, he stated that, from 1932 up to the date of enlistment, he had worked as a farmhand at the Smallicombe farm in Holland, Manitoba, receiving a weekly wage of $6 and his ‘keep’ (food and a place to sleep). He had finished Grade 8 and listed soccer, swimming, and softball as sports he enjoyed.

….Gordon left Canada for overseas service…

Gordon worked as a medical orderly at No. 5 General Hospital in Winnipeg for almost the entire month of January. On January 29, 1940, he boarded a ship in Halifax, Nova Scotia, and with other members of his unit, left Canada for the United Kingdom on January 30, 1940, sailing from Halifax, and disembarking in Gourock, Scotland on February 9, 1940.

No. 5 Canadian General Hospital in Taplow. (Photo source: Eton Wick History)

Once in Great Britain, Gordon continued as a medical orderly, at the 600 bed No. 5 Canadian General Hospital in Taplow, Buckinghamshire, until March 28, 1941. This wartime hospital, which looked after wounded soldiers, was established by the Canadian Red Cross in 1940 and had been built on land donated by the Astor family at their Cliveden Estate.

….Gordon was transferred to the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada…

On March 28, 1941, Gordon was transferred to the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada and sent for advanced infantry training. Then, on January 15, 1942, he was assigned to No. 2 Division Infantry Reinforcement Unit (DIRU) for additional training in preparation for the upcoming Dieppe Raid. On May 1, 1942, he returned to the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada.

On August 18, 1942, Gordon travelled to France with the Regiment, and was part of the combined attack for the Dieppe Raid, known as Operation Jubilee, on August 19, 1942. This was a disastrous Allied amphibious attack on the German-occupied port of Dieppe in northern France. (See https://www.veterans.gc.ca/en/remembrance/military-history/second-world-war/dieppe-raid and https://thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/dieppe-raid)

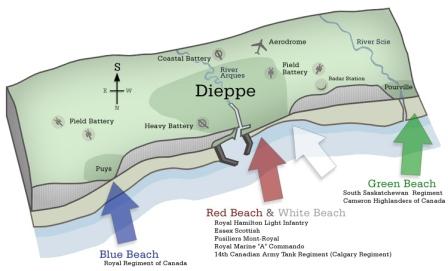

In the battle plan, the South Saskatchewan Regiment was to land in the first wave of the attack on Green Beach to secure the beach at Pourville, the right flank of the operation. The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada would then land in the second wave and move inland along the eastern bank of the Scie River to meet up with the tanks of the Calgary Regiment coming from Dieppe and capture the airfield at Saint-Aubin-sur-Scie. They would then clear the Hitler Battery and attack the suspected German divisional headquarters.

Things didn’t go as planned. While the attack began on time (at 04:50 am) the South Saskatchewan Regiment landed west of the river, instead of in front of it. This didn’t pose a problem for the force aiming to clear the village and attack the cliffs to the west, but for the other force it meant they had to move through the village, cross the exposed bridge over the river before attempting to get on the high ground to the east.

The resulting delay gave the Germans had time to react and deploy, just as the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada came along in their landing craft as the second wave to attack on Green Beach. As they reached 910 metres (1000 yards) off Green Beach, German shore batteries, machine guns, and mortars opened fire.

….Gordon was wounded during the Dieppe Raid…

The main landing at Dieppe had been unsuccessful, and the failure of tanks to arrive made it impossible for the Regiment to gain its objectives. With increased German opposition and no communication with headquarters, the Regiment, which had advanced once reaching the beach, began to fight back to Pourville, carrying their wounded. They made it back and re-established contact with the South Saskatchewan Regiment, only to learn that there was an hour’s wait for the landing craft to return for re-embarkation.

Both the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada and the South Saskatchewan Regiment fought desperately during the wait, but there were too many casualties. At 11:00 am the landing craft began to arrive, taking grievous losses on the approach into the beach. More men were killed and wounded as they tried to board the landing craft under enemy fire. Five landing craft and one tank landing craft managed to rescue men from the shallows and cleared the beach with full loads, but within half an hour, no further rescues were possible.

Of 503 Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada who participated in the raid, 346 were casualties: 60 were killed in action, 8 died of wounds after evacuation, and 167 became prisoners of war (with 8 POWs dying from their wounds). 268 returned to England, 103 of them wounded.

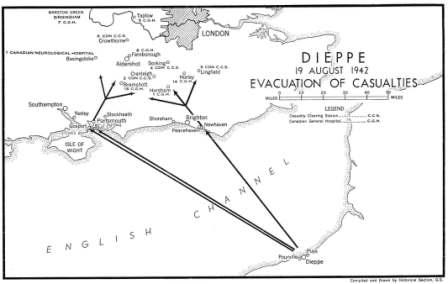

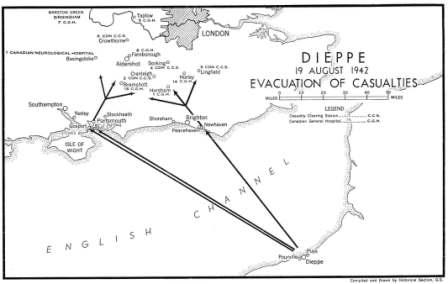

Evacuation of casualties from Dieppe to England on August 19, 1942. (Map source: ‘Official History Of The Canadian Medical Services 1939-1945’)

Gordon was one of the men wounded during re-embarkation. He was evacuated to No. 15 Canadian General Hospital in Bramshott, United Kingdom, with a shrapnel wound to his left ear. According to his hospital file the “….wound penetrated to the bone….” with “…some slight retraction of eardrum… Probably slight concussion as result of artillery fire….” He remained in hospital until August 31, 1942, when the wound healed, and he was able to return to duty.

For his actions during the Dieppe Raid, King George VI was “…graciously pleased to approve that ….” Gordon “…be mentioned in recognition of gallant and distinguished services in the combined attack on Dieppe…” On December 8, 1942, Gordon was promoted to Lance Corporal, remaining in the United Kingdom for further training.

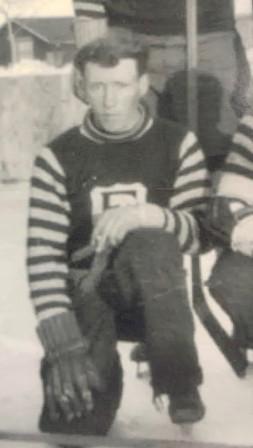

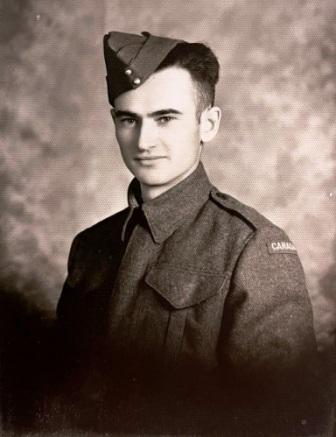

…. Nancy’s son Gordon had a photo of his uncle…

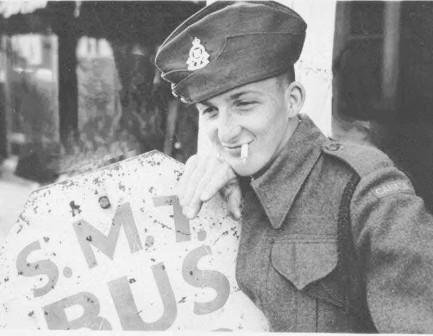

Charles ‘Gordon’ Erickson. (Photo courtesy of Gordon Barker)

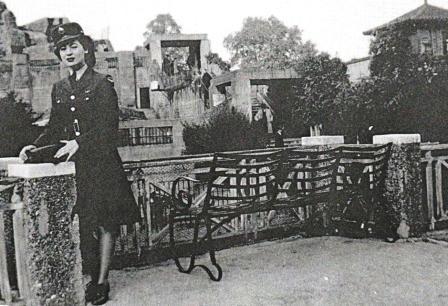

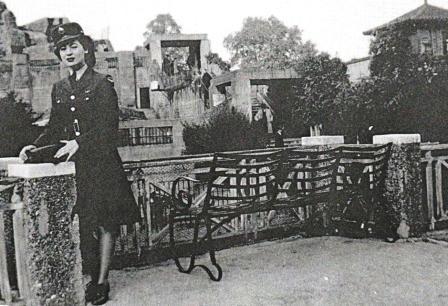

Gordon and his sister Nancy were reunited while both were serving in England. Her son Gordon explained that his mother had joined the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) on August 14, 1942, and served as a secretary for the military in London, England during the war, working on soldiers’ duty assignments and other administrative tasks. He had photos of both his mother and his uncle, who he was named after.

Nancy Erickson in England in 1942. (Photo courtesy of Gordon Barker)

….Gordon was very highly regarded…

Gordon quickly received another promotion, to Corporal, on January 31, 1943. In June 1943, he was sent to No. 5 (Battle) Wing Canadian Training School at Rowland’s Castle, Hampshire, England, for a 4 week Battle Drill course which trained Canadian soldiers in how to react when coming under enemy fire. (See https://www.southdowns.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/The-Canadian-Army-Battle-Drill-School-Stansted-Park-1942.pdf)

The course tried to mimic combat conditions, using obstacle courses and simulated battlefields, live rounds fired over the heads of students, controlled explosions, target practice, and dummies to bayonet.

One of Gordon’s instructors may have been Ralph Schurman BOULTER, whose story was previously told on this blog. (See https://onthewarmemorialtrail.com/2023/03/07/on-the-war-memorial-trail-the-battle-of-bienen-part-2-the-wwii-battle-drill-instructor-from-oleary/)

A September 21, 1943 interviewer wrote in Gordon’s service file that he had “….very high learning ability, a good appearance, and a pleasant personality….” It further noted that Gordon requested “…any courses on supporting infantry weapons…”

….Gordon and the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada arrived in France in July 1944….

The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada Regiment disembarked in Graye-sur-Mer and made their way towards Caen. (Map source: Google maps)

Gordon and the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada Regiment continued training while in the United Kingdom, but on July 5, 1944, a month after D-Day, they left aboard USOS ‘Will Rogers’ from Newhaven, Sussex for Normandy, as part of the as part of the 6th Canadian Infantry Brigade, 2nd Canadian Infantry Division, arriving in Graye-sur-Mer, Calvados, France 2 days later.

By July 12, 1944, Battalion headquarters was based in an orchard near Rots, France, and the troops were dispersed outside of Caen, with the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada sent to Carpiquet. The war diary for that day noted that “…the town was completely demolished. Battalion takes up defence position…”

The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada Regiment were west of Caen in Carpiquet. (Map source: Google maps)

….Gordon was injured during the Battle of Saint André-sur-Orne….

The Battalion was ordered to capture the village of Saint André-sur-Orne, located south-west of Caen. They reached it on July 20, 1944, with rain hindering operations. The Allies faced stiff resistance as they began Operation Spring, a major bombardment that took place on the night of July 24-25, to capture the heights of Verrières Ridge, which overlooks the area between Caen and Falaise. (See https://www.canadiansoldiers.com/history/battlehonours/northwesteurope/verrieresridge.htm)

Part of Operation Spring was the Battle of Saint André-sur-Orne, a village on the starting line of the offensive. It was captured by the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada (6th Infantry Brigade, 2nd Infantry Division) Canadians to the north.

At some point during the battle, Gordon was wounded and evacuated to the United Kingdom for treatment. He remained in the United Kingdom from July 26 to September 23, 1944, after which he returned to his Regiment on September 24, 1944. By now, the Regiment had left France and was in the vicinity of Sint-Job-in-‘t-Goor, in the province of Antwerp, Belgium.

Gordon arrived just after a failed offensive, where Canadian and British troops had tried to secure an undamaged bridge over the Turnhout-Schoten Canal on September 23, 1944. Due to fierce German resistance Allied troops were unable to prevent the enemy from blowing up the bridge.

….The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada were involved in the Battle of the Scheldt….

The Regiment next began preparing to participate in the upcoming Battle of the Scheldt, which began officially on October 2 and lasted until November 8, 1944. The Battle of the Scheldt’s objective was to free up the way to the Port of Antwerp in Belgium for supply purposes. Canadians suffered almost 8,000 casualties (wounded and dead) in what turned out to be the battle with the most Canadian casualties in The Netherlands. (See https://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/history/second-world-war/scheldt)

The War Diary for October 25, 1944 stated that at 9 pm they were ordered to move the next day to an area “…in the Beveland Causeway…”

The Beveland Causeway, also known as the Sloedam, was a narrow land link between South Beveland and Walcheren Island in The Netherlands, crucial for gaining access to the port of Antwerp, and the site of brutal, costly battles in 1944 as Canadian forces fought to secure it against German defenders. This narrow strip, bracketed by marshes, was a heavily defended bottleneck, becoming the focus of fierce assaults.

The War Diary for October 26, 1944 described the challenges faced as they moved into position and were attacked by 88 mm German guns. “…Enemy 88 mm lays direct fire on crossroads as Battalion embusses…..” There were no casualties at this point, but one vehicle was damaged. However, as they moved along the road onto the Beveland Causeway, the convoy was “…mortared as it proceeded…” resulting in a few non-fatal casualties. At 3 pm they were ordered to reverse direction towards the village of Yerseke.

….Gordon lost his life during the Battle of the Scheldt….

The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada moved back from the Beveland Causeway towards Yerseke. (Map source: Google maps)

The War Diary for October 27, 1944 continued to document the struggles faced by the Battalion as they entered Yerseke and took up positions north of the village. The day was “…overcast, visibility poor, light mist, light rain….Battalion enters Yerseke at first light…” They were ordered to cross the canal at a “…small footbridge one company at a time…” The plan was for “…two companies to form bridgehead while two companies push out to take Wemeldinge…”

Things didn’t go according to plan. “…It was found impossible to cross footbridge due to mortars and one 88 mm gun….” At 6:30 pm, Plan B called for “…companies to take up positions along canal bank. Battalion will try crossing by assault boat at 2100 hours…”

While waiting for the assault boats, the men were hit by “…enemy mortars and shells….6 wounded, 2 killed…” The crossing by assault boats didn’t go well, as the 10:30 pm report in the War Diary recorded. “…Battalion attack across canal repulsed by enemy mortar and heavy machine gun fire. Two companies landed on island … All boats but one sunk, that one boat retired two companies to East bank under heavy fire…”

22 year old Gordon was among the fatalities that day, likely one of the two men killed while waiting for the assault boats to arrive.

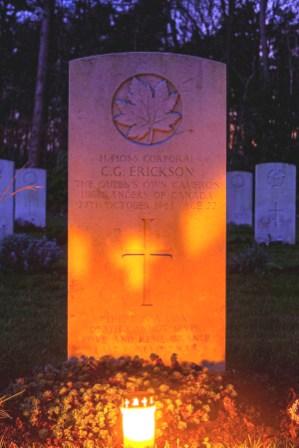

….Gordon is buried in Bergen Op Zoom…

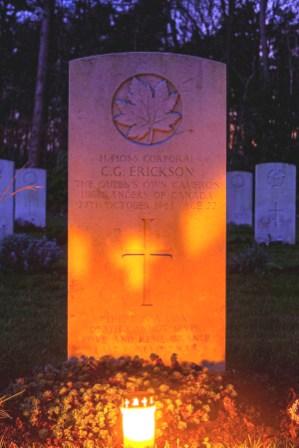

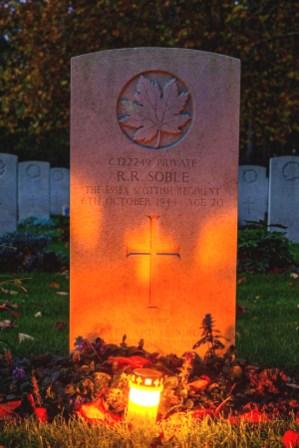

Grave of Charles ‘Gordon’ Erickson in the Canadian War Cemetery in Bergen Op Zoom, The Netherlands with a Christmas Eve candle. (Photo courtesy of Caroline Raaijmakers)

Gordon was temporarily buried on October 31, 1944 in the cemetery in Sint-Maartensdijk, before being reburied in the Canadian War Cemetery in Bergen Op Zoom, The Netherlands on September 5, 1945.

Gordon’s younger sister, Nancy Erickson Vincent, survived the war, had two sons, and lived in Espanola, Ontario until her death in 2014. His older sister, Hazel Francis Erickson Kerr, lived in St Thomas, Ontario, but had died by the time she was found by Nancy’s son Gordon Barker in 2006.

By then, Nancy had fallen ill with dementia. “….I didn’t tell her that I found her sister because her sister had already passed away by that time….” he said. “…With the dementia and everything going on, I didn’t want to cause her any more pain…”

Thank you to Shawn Rainville for newspaper searches, and to Judy Noon of the Royal Canadian Legion Branch 39 in Espanola, Ontario for contacting Gordon Barker. A big thank you goes to Gordon Barker for providing photos and information, and to Kevin Rollason for writing a newspaper article highlighting the search for a photo.

Gordon Barker in Bogor, Indonesia. (Photo courtesy of Gordon Barker)

If you have photos or information to share about soldiers buried in The Netherlands or Belgium, please email him at memorialtrail@gmail.com, or comment on the blog.

© Daria Valkenburg

….Want to follow our research?…

If you are reading this posting, but aren’t following our research, you are welcome to do so. Our blog address: https://onthewarmemorialtrail.com/

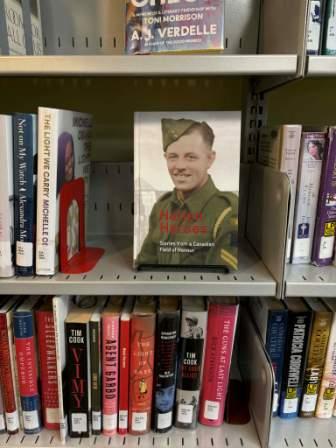

4 countries, 6 weeks, 7,000 km – an unforgettable war memorial journey in Europe…. Daria’s book ‘No Soldier Buried Overseas Should Ever Be Forgotten‘ is available in print and e-book formats. Net proceeds of book sales help support research costs and the cost of maintaining this blog. For more information see https://nosoldierforgotten.com/

4 countries, 6 weeks, 7,000 km – an unforgettable war memorial journey in Europe…. Daria’s book ‘No Soldier Buried Overseas Should Ever Be Forgotten‘ is available in print and e-book formats. Net proceeds of book sales help support research costs and the cost of maintaining this blog. For more information see https://nosoldierforgotten.com/

Subscribe to our YouTube Channel: On The War Memorial Trail With Pieter Valkenburg: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCJ591TyjSheOR-Cb_Gs_5Kw.

Never miss a posting! Subscribe below to have each new story from the war memorial trail delivered to your inbox.

4 countries, 6 weeks, 7,000 km – an unforgettable war memorial journey in Europe…. Daria’s book ‘No Soldier Buried Overseas Should Ever Be Forgotten‘ is available in print and e-book formats. Net proceeds of book sales help support research costs and the cost of maintaining this blog. For more information see https://nosoldierforgotten.com/

4 countries, 6 weeks, 7,000 km – an unforgettable war memorial journey in Europe…. Daria’s book ‘No Soldier Buried Overseas Should Ever Be Forgotten‘ is available in print and e-book formats. Net proceeds of book sales help support research costs and the cost of maintaining this blog. For more information see https://nosoldierforgotten.com/

Thank you also to Maarten Koudijs for information on Peter’s death and the names of the other South Saskatchewan Regiment casualties. (Information on his book, available in Dutch, can be found at

Thank you also to Maarten Koudijs for information on Peter’s death and the names of the other South Saskatchewan Regiment casualties. (Information on his book, available in Dutch, can be found at