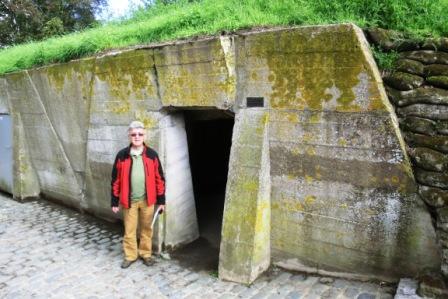

Daria outside the pavilion at Berks Community Cemetery in Belgium. The Extension is to the left. (Photo credit: Pieter Valkenburg)

December 31, 2025. While in Belgium during our 2025 European War Memorial Tour, we were joined by Pieter’s cousin François Breugelmans and his wife Mieke de Bie.

We visited Zonnebeke and were successful in finding the location of the original burial of WWI soldier Vincent Earl CARR of Prince Edward Island who was killed during the Battle of Passchendaele in October 1917. (See https://onthewarmemorialtrail.com/2025/12/22/on-the-war-memorial-trail-the-search-for-the-trench-where-wwi-soldier-vincent-carr-was-originally-buried/)

We also visited Ostende New Communal Cemetery to lay flags at the grave of Manitoba-born WWII soldier Donald David MacKenzie TAYLOR, who drowned when the Landing Ship Tank LST- 420, carrying members of No. 1 Base Signals and Radar Unit (BSRU), sank after it hit a mine near the harbour in Ostend, Belgium. (See https://onthewarmemorialtrail.com/2025/12/27/on-the-war-memorial-trail-the-wwii-soldier-born-in-manitoba-who-lost-his-life-when-lst-420-hit-a-mine-in-the-harbour-outside-ostend/)

The final stop on the Belgian portion of our trip was to visit Berks Cemetery Extension in Ploegsteert not far from Ypres, and almost at the French border. Our goal was to place flags at the graves of two WWI soldiers….

….Request from a Belgian researcher…

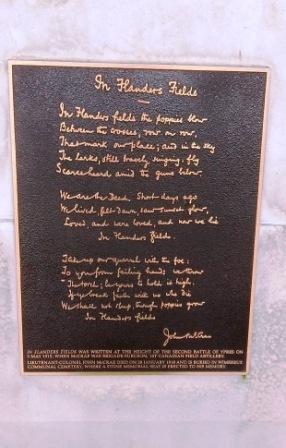

On April 4, 2025, just as we were preparing for our 2025 European War Memorial Tour, Belgian researcher Patrick Michiels had written us, asking for help in “….finding photos for two WWI soldiers buried in Berks Cemetery Extension in Komen-Waasten (near Ploegsteert). We’ve in total about 20 adopted soldiers in this Cemetery with our group of Friends…”

He went on to explain that the two soldiers were Captain George Pigrum BOWIE, a well-known architect in Vancouver, British Columbia, who had been born in England, and Private Warren GILLANDER of Athelstan, Quebec. “…Berks Cemetery Extension has only WWI casualties ….”

We agreed to help once we returned from Europe. In the meantime, with help from Judie Klassen and Shawn Rainville, initial research began on George Pigrum Bowie. We thought that it might be easier to find a photo of him, since he was an architect, and we hoped to have a photo before we visited the cemetery. In the end, we didn’t find a photo of either soldier while we were in Europe.

….A photo of George was found…

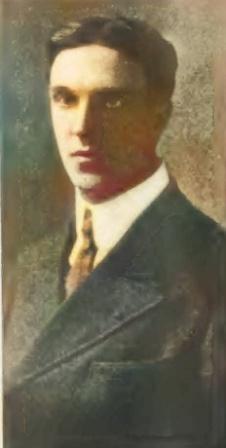

Months after our trip, we learned of a photo of George in the Journal of the Royal Institute of British Architects in the July 31, 1915, Volume 22, Issue 17, and with the help of the Prince Edward Island Library Service, a copy of the journal was found.

George Pigrum Bowie. (Photo source: July 31, 1915 issue of the Journal of the Royal Institute of British Architects. Photo colourization by Pieter Valkenburg)

….George Bowie was a true Renaissance man …

Born on March 29, 1881 in Upper Holloway, London, England, George was the eldest son of Alfred Henry and Elizabeth Bowie. He became a draftsman with Holloway Brothers, a building firm in London, staying with the firm from 1896 until 1901, gaining a good knowledge of construction, which would be very useful as an architect. George studied at the City of London College and trained under architect Edward Prioleau Warren. (See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Prioleau_Warren)

In 1904, he worked for a short period in Boston, Massachusetts, USA, for Russell Sturgis and for C.A. Cummings, before returning to England in early 1905 as an assistant to Charles Harrison Townsend. (See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Harrison_Townsend)

After immigrating to Canada in 1906, George was employed as chief assistant at Parr & Fee in Vancouver, British Columbia, working there until 1910 when he opened his own firm.

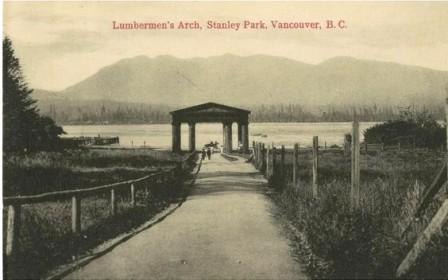

Postcard of Lumberman’s Arch, designed by George Pigrum Bowie, circa 1913.

In 1912 he designed the Lumberman’s Arch of Welcome in Vancouver for the Lumbermen and Shinglemen of Vancouver in honour of the visit of the Duke of Connaught, the Governor General of Canada at the time. Envisioned as a temporary structure to be placed downtown at Pender Street and Hamilton Street, it was a massive timber structure constructed entirely of fir, held together only by its own weight as no nails, bolts or fasteners were used.

After the Governor General’s visit, however, the arch was not destroyed. Instead, it was taken down, floated across Coal Harbour, and relocated in Stanley Park in March, 1913. After George’s death in 1915 it was renamed Bowie’s Arch and remained until 1947 when, due to rotting timbers, it was replaced by a simpler structure which still stands in Stanley Park. Over the years, I’ve been in Stanley Park many times, and likely saw Bowie’s Arch – and never realized it’s significance! (See https://vancouversun.com/news/local-news/this-week-in-history-1947-lumbermens-arch-is-demolished)

In 1907, George joined the Freemasons. Judie Klassen, who tracked all the activities he was involved in, wrote to say “…I didn’t realize the breadth of information that I would find when I started looking into newspaper articles for this soldier…” He was well known, not only professionally, but also “… in charitable, church and social circles. He belonged to the Vancouver Riding Club, the YMCA, the Vancouver Rowing Club, a fencing club, the Vancouver Automobile Club. He also belonged to Christ Church and taught bible classes or Sunday school…”

George was engaged to Alice Margaret Scott, who had grown up in Saint John, New Brunswick, giving this west coast story a Maritime twist!

After we returned from Europe, an undated and unattributed photo from the fencing club was found by Judie.

Left to right (back row): W. Walken, B.F. Wood, H.J. Cave, W. Pumphrey and G.H. Henderson; (middle row): A. Rowan, G. Sheldon, W. McC. Hutchison, W. McNaught, E. Cook, G. Bowie (identified by yellow arrow) and J. Johnstone; (front row): M. Alpen, P.R. West, Olive Trew, Mrs. C.F. Cotton, F. Cowens and J.E. Parr. (Photo source unknown)

….George enlisted in 1914 …

Canada entered WWI on August 4, 1914, the same day that the United Kingdom declared war on Germany. A month later, George enlisted. At the time of his enlistment with the Canadian Overseas Expeditionary Force on September 23, 1914 in Valcartier, Quebec, George was assigned to the 5th Canadian Infantry Battalion as a Sergeant. He had already served for three years with the 20th Middlesex Rifles, and was an active member of the 31st British Columbia Horse, a militia regiment. (See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_Columbia_Hussars)

On October 20, 1914, George arrived in the United Kingdom from Canada. The 5th Canadian Infantry Battalion War Diary for that day noted that “…the Battalion disembarked at full strength at Devonport….” and began making its way to Salisbury Plain.

Map showing the 706.5 km route across the English Channel from Avonmouth to Saint-Nazaire. (Map source: Google maps)

Training continued in England until February 11, 1915, when the Battalion boarded the HMT Lake Michigan in Avonmouth on February 11, 1915, arriving in St. Nazaire, France 2 days later. By February 23, 1915, they were digging trenches in Armentieres, and encountering German snipers.

April 1915 found the Battalion had moved into Belgium, near Ypres, and were under heavy fire, with many casualties, during the Second Battle of Ypres, which was fought from April 22 to May 15, 1915. By April 24, 1915 the Germans attacked with poison gas, as well as artillery. (See (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second_Battle_of_Ypres)

On May 15, 1915 George, who was a Sergeant with ‘A’ Company of the 5th Canadian Infantry Battalion, was promoted to Lieutenant, but given a temporary commission to Captain. His bravery and leadership skills didn’t go unnoticed.

….George wrote about the Battle of Festubert….

1919 photo of the ruined landscape near Festubert, 4 years after the May 1915 battle. (Photo source: Canadian War Museum)

In the latter part of May 1915, the Battalion was engaged in the Battle of Festubert, and suffered devastating losses. George was in this battle and wrote a letter to the Daily News Advertiser newspaper on May 26, 1915, describing how he crawled through an open gap between trenches to find whether a certain trench was held by Canadians or Germans, and then had to make a new connecting trench through the gap by piling dead Germans along either side. The letter was published on June 20, 1915, just a few short weeks before George lost his life. (See https://www.canadiansoldiers.com/history/battlehonours/westernfront/festubert.htm)

“…At about five a.m. the general sent for me and gave me orders to take up my men and, as I had taken the precaution to have them sleep fully equipped, they were soon ready. It was now broad daylight, and we had to be very careful to avoid observation from aeroplanes and the enemy’s lookout.

I had to report to a certain officer but he was wounded and so were several others in order of seniority, so I finally decided I would report to one of our own company officers, but no one could tell me when or where our men were.

There were vague rumours that the Germans had cut them off, surrounded them, were driving them back away from us, etc, but I could get no definite information, so I put my men to work to improve the trenches where they were. It was a bad place and filled with dead and wounded men….and I wanted to take my men’s minds off their troubles by getting them to dig in and get cover from the very severe shell fire, which was killing and wounding men all the time.

After moving around in various positions I found a trench at the other end of which were supposed to be our own men with Germans in between. I went along and discovered a big portion of a trench had been blown up by the Germans as soon as our men occupied it, and on the far side of the gap were men who were variously reported to be Germans or Canadians.

I did the caterpillar act, and crawled across the opening….and eventually reached the position our men were holding. I found all the officers dead or wounded, and a lot of the men were also hurt, but the survivors were happy as clams at high tide and ready to hold the place against anything.

I told them we had lots of reinforcements and food and ammunition and would connect up with them…. It was funny to see me diving head first into shell holes and crawling along like a cat after a sparrow…

I found by this time that I was the only Canadian officer of our battalion alive and unwounded in our trenches….” which were “…in a terrible state.…”

With so many wounded, and no officer in charge, George took over, writing that “…we moved down one of the trenches towards the gap … and began work by piling dead Germans, their kits and their sandbags into the open spaces made in the sides of the trench by shells, so that the enemy would not see us moving along the trench. Then we began digging a foxy little trench toward our friends, but in such a manner that the enemy could not see. Also we passed up all the German food and comforts in the old German trenches, so that we should be able to give our lads some food….”

George found that, contrary to reports they’d received, German troops were well fed, based on what they found in the trenches. “….We found rye bread, German sausage, cold bacon, candy, chocolates, cigars, cigarettes, very rich cake, jam and a sort of lard, while all the water bottles were filled with coffee…

We got back to our billets about 4 a.m. yesterday. An officer was asked to take out a burial party to bring in our dead officers and what men we could get, so I went. It was an unpleasant job, but we got them without losing one of our party. Of course, there are many left. We are going out again tonight to try and get some more. We have made a graveyard near here and put up wooden crosses over the graves….”

The War Diary for May 25, 1915 confirmed that George had led a burial party. A “…volunteer party under Lt G. P. Bowie went out at 9 pm, returning at 4:30 am, to bury dead and recover sentimental effects…” This was repeated the following evening into early morning. By now, the Battalion had moved back across the border into France and was based in Essars.

….George was killed by a sniper’s bullet…

On June 25, 1915, the Battalion moved back across the border into Belgium, near Ploegsteert. Soldiers were busy deepening and improving trenches, refurbishing the wire in No-Mans-Land, and dealing with enemy snipers and ongoing rifle fire.

On July 7, 1915, at the age of 34, George lost his life, killed by a German sniper’s bullet while sketching trenches, part of his duties. Pte H. KELLY was wounded. An April 28, 1919 article in Vancouver Daily World quoted Mr. S. Lucas who said that “…before he was shot he realized his danger and sent back to safety the men with him…”

….George was buried in Chateau Rosenberg Military Cemetery …

Temporary burial place of George Pigrum Bowie (to the right of the soldier) in Chateau Rosenberg Military Cemetery. (Photo Courtesy of Brett Payne)

George was initially buried in Chateau Rosenberg Military Cemetery, about 1 km north-west of Berks Extension Cemetery, and his headstone included a freemason’s mark (square and dividers/compasses). A photo was found of his grave, with a soldier standing between his grave and that of Pte Albert Eber Gustav GABBE, on a site written by Brett Payne of Tauranga, New Zealand. (See https://photo-sleuth.blogspot.com/2008/09/canadian-war-graves-ed-pye-and-5th.html)

When I contacted him, he explained that he believed the man in the photo was his “… grandfather’s friend Ed Pye. Arthur Edwin Pye (1893-1960) originally enlisted in the 60th Rifles at Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan on 12 August 1914, and five weeks later was attested into the 11th Battalion at Valcartier….”

Based on Ed Pye’s service record, Brett thought that the photo dates to “…the spring or summer of 1916….” and that the photo was “…taken next to these particular graves because they were of men that he had served with the previous year….”

….George was reburied in Berks Cemetery Extension…

In March 1930, 475 graves were moved from Chateau Rosenberg Military Cemetery when the land for Berks Cemetery Extension was granted in perpetuity. The land at Chateau Rosenberg did not have this guarantee. The cemetery grounds at Berks were assigned to the United Kingdom in perpetuity by King Albert I of Belgium in recognition of the sacrifices made in the defence and liberation of Belgium during the war.

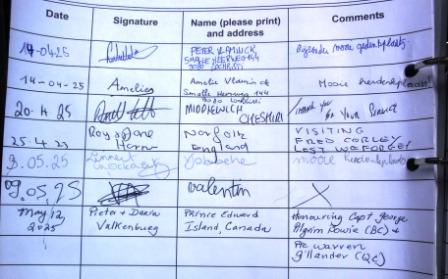

95 years later, we visited the cemetery to honour George Pigrum Bowie and Warren Gillander. As usual, we wrote in the visitors’ book.

Entry in the visitors’ book. (Photo credit: Daria Valkenburg)

Pieter placed a Canadian flag at George’s grave.

Pieter behind the grave of George Pigrum Bowie. (Photo credit: Daria Valkenburg)

….A photo of Warren Gillander has yet to be found…

At the grave of Warren Gillander, whose photo has yet to be found, Pieter placed flags of Canada and Quebec.

Pieter at the grave of Warren Gillander. (Photo credit: Daria Valkenburg)

Pieter stands behind the grave of Warren Gillander. (Photo credit: Daria Valkenburg)

The flags placed these two graves were donated. Our thanks go to:

- Alan Waddell, Constituent Assistant, on behalf of Heath MacDonald, MP for Malpeque, for the Canadian flags.

- Mario Henry and his brother Etienne Henry, who donated the Quebec flag.

Thank you to Judie Klassen and Shawn Rainville for the extensive research and newspaper searches. Thank you to the Prince Edward Island Library system for helping to access the journal in which a photo of George Pigrum Bowie was found. Thank you to Brett Payne for the photo from Chateau Rosenberg Cemetery. Thank you also to François Breugelmans and Mieke de Bie for joining us on the Belgian portion of our visit.

Our adventures continue as we return to The Netherlands for the next portion of our 2025 European War Memorial Tour.

If you have a story or photo to share, please contact Pieter at memorialtrail@gmail.com or comment on the blog.

© Daria Valkenburg

….Want to follow our research?…

If you are reading this posting, but aren’t following our research, you are welcome to do so. Our blog address: https://onthewarmemorialtrail.com/

4 countries, 6 weeks, 7,000 km – an unforgettable war memorial journey in Europe…. Daria’s book ‘No Soldier Buried Overseas Should Ever Be Forgotten‘ is available in print and e-book formats. Net proceeds of book sales help support research costs and the cost of maintaining this blog. For more information see https://nosoldierforgotten.com/

4 countries, 6 weeks, 7,000 km – an unforgettable war memorial journey in Europe…. Daria’s book ‘No Soldier Buried Overseas Should Ever Be Forgotten‘ is available in print and e-book formats. Net proceeds of book sales help support research costs and the cost of maintaining this blog. For more information see https://nosoldierforgotten.com/

Subscribe to our YouTube Channel: On The War Memorial Trail With Pieter Valkenburg: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCJ591TyjSheOR-Cb_Gs_5Kw.

Never miss a posting! Subscribe below to have each new story from the war memorial trail delivered to your inbox.