August 14, 2021. In researching the service of many courageous air crew who lost their lives during WW2, Pieter Valkenburg, who served in the Dutch Air Force, thought how much he would have liked to talk to them. So, Pieter was pleased when a trip to Kinkora for ice cream and a visit with Bonnie Rogerson of Chez Shez Inn led to us meeting RCAF pilot Captain Scott NANTES. (RCAF is the acronym for Royal Canadian Air Force.)

Scott was on the Island with his husband Felix Belzile for a short family visit, and told us that “…My mother Rhonda is from Kinkora and still lives here with my stepfather, Damien Coyle….” His father, Michael Croken, lives in Moncton, New Brunswick.

Felix Belzile (left) and Scott Nantes (right). (Photo credit: Daria Valkenburg)

Growing up in Kinkora, Scott was a member of the Royal Canadian Air Cadet Program 53 Squadron in Summerside. “…It was through the Air Cadets that I received my glider and private pilot’s licence…” he said.

….The military covered the cost of tuition….

For the best chance of having a career in flying, he applied to the ROTP (Regular Officers Training Plan), a program that would give him an opportunity to earn a fully paid university degree and an officer’s commission in the Canadian Armed Forces, in return for a commitment to serve for a set period. (For more information, see https://www.rmc-cmr.ca/en/registrars-office/regular-officer-training-plan-rotp)

Scott was accepted into the program and began his first year of studies at the Royal Military College Saint-Jean (Collège militaire royal de Saint-Jean) in Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu, Quebec, 40 km south of Montreal. (See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_Military_College_Saint-Jean)

After the first year in Quebec, Scott continued his studies at the Royal Military College in Kingston, majoring in Political Science. (See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_Military_College_of_Canada) This is where he met Felix, who majored in Computer Engineering. Both men were enlisted in the RCAF.

….Basic Flight Training gives an indication of who has the ‘right stuff’….

After receiving his Bachelor of Arts, Scott was sent to Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan for 1 year of Basic Flight Training, even though he already had a private pilot’s licence. “…This is an RCAF requirement, even for commercial pilots, as there are differences from non-military pilot training. You are trained in formation flying, low level navigation, and aerobatics…” he explained.

While operational skills are essential, this period is where trainees are assessed on other characteristics that make a good military pilot. “…Decision making is key…” Scott noted. “…You can’t freeze up, as you must think quickly. Training sorts out who can handle stress…”

Following this basic training, pilots are chosen for one of three streams: fighter pilot, helicopter pilot, or multi-engine pilot. Scott’s first choice of multi-engine pilot was accepted, and he spent a further 5 months in Portage La Prairie, Manitoba, for multi-engine training on a King Air C90. “…Here we learned to deal with a 2 person crew. I received my wings in February 2015….”

….Flying the Airbus A310 …. even into a war zone….

Scott Nantes in front of an Airbus A310 at the 2018 Air Show Atlantic in Summerside. (Photo courtesy Scott Nantes)

After receiving his wings, Scott was selected to fly the Airbus A310 (which has the military designation Polaris CC150) and was based in Trenton, Ontario. This plane is used for three main functions: VIP transport, air to air refueling, and regular troop transport.

Scott gave examples of his experience with VIP transport. “…I flew Prime Minister Trudeau to the first meeting with former US President Trump in Washington in 2017, and took former Governor General David Johnson on his last flight to China…”

Regular troop transport included flying troops to and from bases in Edmonton or Quebec City and overseas bases in Kuwait, Latvia, and Ukraine.

Scott Nantes in the cockpit of an Airbus A310 in Kuwait. (Photo courtesy Scott Nantes)

Scott had three deployments to Kuwait as an air to air refueling pilot, flying into Iraq and Northern Syria during the ISIS Coalition. Each deployment lasted 2 months. Air to air refueling has been described as a ‘gas station in the sky’, where a plane with the fuel must connect with a plane requiring fuel, through a probe that attaches to each plane. It’s like something out of a science fiction movie! As someone who finds threading a sewing needle a challenge, I could only marvel at the skill required.

During this period, he and Felix had a long-distance relationship. Felix explained that “…I was posted to Ottawa after receiving my Computer Engineering degree, and then started a software business on the side. This turned into a full-time business after leaving the RCAF in 2017 and I was able to follow Scott to Trenton….”

….A new challenge in flying the Challenger….

In 2020, Scott received a new assignment and was posted to Ottawa, where he and Felix currently live. “…Now I’m flying the Challenger 604 and the new Challenger 650 planes, which are used for VIP and Medivac transport…”

A passion for flying led Scott Nantes to a rewarding career serving our country and we thank him for sharing his story. If you have a story or photos to share, please contact Pieter at dariadv@yahoo.ca, comment on the blog, or send a tweet to @researchmemori1.

….Want to follow our research?….

If you are reading this posting, but aren’t following the blog, you are welcome to do so. See https://bordencarletonresearchproject.wordpress.com or email me at dariadv@yahoo.ca and ask for an invitation to the blog.

You are also invited to subscribe to our YouTube Channel: On The War Memorial Trail With Pieter Valkenburg: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCJ591TyjSheOR-Cb_Gs_5Kw.

© Daria Valkenburg

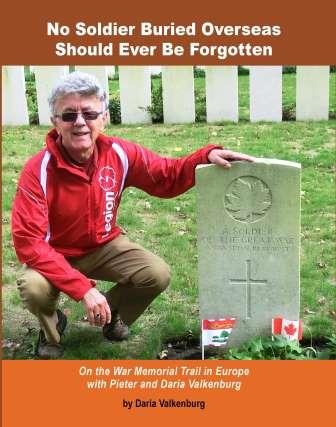

4 countries, 6 weeks, 7,000 km – an unforgettable war memorial journey in Europe….

4 countries, 6 weeks, 7,000 km – an unforgettable war memorial journey in Europe….