January 14, 2023. Several years ago, when Pieter was researching the names listed on the Cenotaph outside the Borden-Carleton Legion, the story of WWII Flight Officer Joseph “Joe” Charles MCIVER of Kinkora, Prince Edward Island, was told.

Joe was posted to RAF Coastal Command, a formation with the Royal Air Force (RAF), which had a mandate to protect convoys from German U-boats and Allied shipping from aerial threats from the German Air Forces. Squadrons operated from various bases, including in the Arctic Circle.

Joseph Charles McIver. (Photo: The Canadian Virtual War Memorial – Veterans Affairs Canada)

Joe’s nephew, Alan A. McIvor, wrote a book on his uncle called ‘United In Effort…Flying Officer Joseph Charles McIver…Royal Canadian Air Force…1940-1944’. One of the documents in the book was a letter Joe wrote to his wife Helen from the far north of the Soviet Union (now Russia) on September 23, 1942. Joe’s actual location in the letter was erased by censors, but his heading ‘Somewhere In North Russia’ was left intact.

We were reminded of the letter when we met Lorna Johnston, Alan’s cousin, and she gave us a copy of the same letter.

…Joe McIver’s Squadron participates in Operation Orator ….

Map shows the location of the Barents Sea north of Russia and Norway, and the surrounding seas and islands. (Map created by Norman Einstein, 2005. Courtesy of https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Orator#/media/File:Barents_Sea_map.png)

On September 4, 1942, Joe McIver was in the Royal Australian Air Force’s (RAAF) 455 Squadron with a group flying to the Soviet Union as part of ‘Operation Orator’, a search and strike force to operate over the Barents Sea. The plan was to fly on a course to reach Norway, cross the mountains in the dark, overfly northern Sweden and Finland, and land at Afrikanda air base, at the southern end of Murmansk Oblast (an oblast is similar to a province). (See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Orator for more information on Operation Orator and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Afrikanda_(air_base) for more information on Afrikanda.)

…Joe’s plane ran out of fuel and crashed ….

As Joe explained in his September 23, 1942 letter “…we were at 8,000 feet and below us were solid clouds and not a break in them. We couldn’t come down for fear of crashing into a mountain. So we decided to fly to the White Sea and follow it up, which we did, and finally came to our destination….but there was no aerodome in sight...”

Then they realized they were running out of fuel! “…Our fuel was getting very low and we started to look for a half decent paddy to set down on. We spotted a marshy field and were running up to it when both motors cut out of gas, and down we went in a woods…”

All five crew members got out safely, thankful that the plane “…didn’t go up in flames as we expected…Nobody said much for five minutes….”

They were soon met by 15 Soviet soldiers who at first mistook them for Germans. “…This was the first time I was scared, knowing we were close to the front line and that they couldn’t understand us. It was the first time for me to put my hands up while I was being searched and I put them up good and high!…”

After establishing that they were Allied airmen, the Soviets “…got a truck and took us to a Military Camp and gave us a bang up dinner…” After dinner, they were taken to where the rest of the Squadron were housed.

They stayed for a few days and were allowed to look for their personal belongings on the downed plane. Then, with the aid of an interpreter, they travelled by train and truck “…for the drome from which we are going to operate. We have no aircraft so there’ll be no operations for us unless somebody gets sick or hurt….”

Their journey took them 190 km to Vayenga, located on the coast of the Barents Sea along the Kola Bay 25 kilometers (16 miles) northeast of Murmansk.

Vayenga, now called Severomorsk, is the main administrative base of the Russian Northern Fleet. During WWII, a naval airfield built in a neighbouring bay was used by the British, namely No. 151 Wing RAF, to protect the Arctic.

…Joe’s letter from the Arctic Circle ….

Joe’s Squadron was in Vayenga for just over a month. In his letter, he included his impressions of life in the far north. “…Up here we are eating RAF supplies and not Russian food. We spend most of our time reading, cutting wood. We’re in the Arctic Circle and it’s getting fairly cool!…”

Joe hoped they would be sent back to England soon. “…We expect to get back soon. If we don’t soon go, I think I’ll get into a dugout. I’ll be glad to get back to get some letters, English papers, radio, etc. Everybody’s in uniform here! No leave until Victory!….”

Although they got an allowance from the Soviets, “…there’s absolutely nothing to buy. One can spend a few roubles for a shave now and again…”

Of course, no trip to the Soviet Union would be complete without trying what their Soviet colleagues drank to keep warm. “…I’ve had one drink of vodka and it’s sudden death! Summerside’s screech is mild compared to it….” Vodka’s high alcohol content can warm the body, helpful when temperatures are below freezing point!

Joe and his Squadron may have been in the far north, but they were still subject to enemy attacks. “…I have spent quite a few hours in the air raid shelters. I never thought I could run so fast. I can pass anybody on the way to the shelter…”

The day before he wrote his letter, he noted that “…during a dog fight yesterday over the aerodome, an aircraft was shot up. The pilot bailed out and the aircraft came down and crashed in the building. There were no people in it at the time. Lots of excitement every day!…”

Joe summarized the trip by saying “…this trip has been a great experience, one that I wouldn’t have missed for the world, but I wouldn’t want to do it again. That crash landing, the first meeting with the Ruskies, and the first Russian meal are incidents I’ll always remember…”

…Joe did not survive WWII….

In October 1942 Joe’s Squadron returned to England, but it wasn’t long before Joe found himself back in the Arctic Circle. On November 18, 1944, Joe was part of the crew of Liberator MK VA EV-895, which took off on anti-submarine patrol looking for a suspected U-boat off Gardskagi, Iceland.

Unfortunately, the plane disappeared over the Arctic Ocean and was never seen again. (See https://onthewarmemorialtrail.com/2019/08/17/the-ww2-flight-officer-whose-plane-went-down-while-on-patrol-near-the-arctic-circle/)

Thank you to the Alan McIvor and Lorna Johnston for sharing Joe McIver’s letter from Russia, which provided a glimpse into what he experienced in his own words. If you have a story to share, please contact Pieter at memorialtrail@gmail.com, comment on the blog, or tweet to @researchmemori1.

© Daria Valkenburg

…Want to follow our research?….

If you are reading this posting, but aren’t following the blog, you are welcome to do so. Our blog address: https://onthewarmemorialtrail.com/.

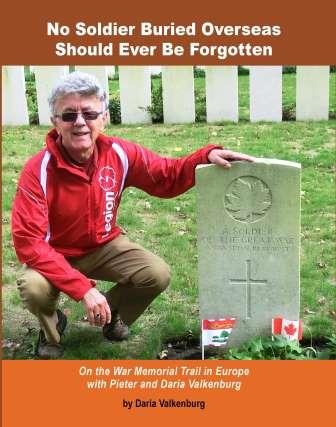

4 countries, 6 weeks, 7,000 km – an unforgettable war memorial journey in Europe…. Daria’s book ‘No Soldier Buried Overseas Should Ever Be Forgotten‘ is available in print and e-book formats. Net proceeds of book sales help support research costs and the cost of maintaining this blog. For more information on the book, please see https://nosoldierforgotten.com/

4 countries, 6 weeks, 7,000 km – an unforgettable war memorial journey in Europe…. Daria’s book ‘No Soldier Buried Overseas Should Ever Be Forgotten‘ is available in print and e-book formats. Net proceeds of book sales help support research costs and the cost of maintaining this blog. For more information on the book, please see https://nosoldierforgotten.com/

You are also invited to subscribe to our YouTube Channel: On The War Memorial Trail With Pieter Valkenburg: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCJ591TyjSheOR-Cb_Gs_5Kw.

Never miss a posting! Subscribe below to have each new story from the war memorial trail delivered to your inbox.