CWGC Volunteer Pieter trying to activate the Work App at Cape Traverse Community Cemetery. (Photo credit: Daria Valkenburg)

August 8, 2025. Anyone who has visited a War Graves Cemetery managed by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) can attest to how well the graves are cared for and the incredible work done by the gardeners in ensuring that flowers and small shrubs are planted in each row of graves.

And yes, the grass is kept green and well-watered, as we ourselves experienced while visiting one of the Canadian War Cemeteries in The Netherlands on a very hot day. It wasn’t that I minded getting drenched, but I didn’t appreciate my carefully written spreadsheet of the graves to visit getting water-soaked!

We knew that the CWGC commemorates and cares for the graves of men and women of the Commonwealth that died during WWI and WWII, but were astounded to learn that this involves 1.7 million graves. Six member countries make up the CWGC– the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India, and South Africa.

According to the CWGC website, “… 23,000 locations in over 150 countries and territories….” are covered with “…. over 2,000 ‘constructed’ war cemeteries the largest being Tyne Cot in Belgium….” – which we had visited in 2017.

….Who is commemorated in a CWGC grave?…

CWGC commemorates personnel who died between August 4, 1914 and August 31, 1921 for WWI and September 3, 1939 and December 31, 1947 for WWII, while serving in a Commonwealth military force or specified auxiliary organization.

CWGC also commemorates those who died in the same WWI and WWII time period as above, after they were discharged from a Commonwealth military force, if their death was caused by their wartime service.

Commonwealth civilians who died between September 3, 1939 and December 31, 1947 as a consequence of enemy action, Allied weapons of war, or while in an enemy prison camp are also commemorated.

….Pieter is now a volunteer under CWGC’s National Volunteer Program…

Not all Canadians who died during WWI or WWII are buried overseas. They may have died of illness or accidents and were buried in Canada, but still have a CWGC gravestone. Recently the CWGC asked for volunteers across Canada to be part of the National Volunteer Program and visit local cemeteries and gather information about the condition of CWGC war graves.

Having visited so many CWGC cemeteries, as well as CWGC graves in municipal cemeteries, in Europe, Pieter applied and was accepted as a volunteer. After receiving training on how to inspect headstones, how to report a grave in need of repair, and how to safely clean headstones where required, he was assigned 4 cemeteries in the South Shore area on Prince Edward Island. The 4 cemeteries are:

- Cape Traverse Community Cemetery (3 CWGC graves)

- Tryon People’s Cemetery (2 CWGC graves)

- Kelly’s Cross (St Joseph) Parish Cemetery (1 CWGC grave)

- Seven Mile Bay (St Peter’s) Cemetery (4 CWGC graves)

….There are 3 CWGC graves at Cape Traverse Community Cemetery…

Pieter with Rev Kent Compton outside the Free Church of Scotland in Cape Traverse. (Photo credit: Daria Valkenburg

Cape Traverse Community Cemetery, formerly known as the Free Church of Scotland Cemetery, was first on Pieter’s list. A sub-committee of the Cape Traverse Ice Boat Heritage Incorporated maintains the cemetery on behalf of the Free Church of Scotland. “…The church is still responsible for the cemetery and owns the land….” explained Reverend Kent Compton.

Jim Glennie (left) and Andrew MacKay (right) with Pieter Valkenburg (centre). (Photo credit: Daria Valkenburg)

“…This is the third summer that we’re cutting the grass at the cemetery…” reflected Andrew MacKay. Andrew and Jim Glennie, two volunteers with the organization, said that the organization had been approached for help by older parishioners in the community.

….Three CWGC graves were inspected at Cape Traverse Community Cemetery…

There are 3 CWGC graves in this cemetery, whose stories have all been told over the years on this blog:

- 18 year old WWII soldier Harold ‘Lloyd’ LEFURGEY of North Bedeque was undergoing basic infantry training at No 70 Canadian Infantry (Basic) Training Centre in Fredericton, New Brunswick, when he fell ill with acute appendicitis. He was rushed to Fredericton Military Hospital on March 17, 1945, but died on the operating table before the operation actually started. (See https://onthewarmemorialtrail.com/2020/05/23/the-young-ww2-soldier-who-lost-his-life-on-the-operating-table/)

- WWI soldier Elmyr KRUGER was born in Melita, Manitoba, but moved to Saskatchewan with his family as a child. While serving with the 232rd Battalion, he was assigned to the 6th Battalion Canadian Garrison Regiment for escort duty, overseeing German Prisoners of War from the Amherst Internment Camp, who were assigned to a work detail for the railway in Borden. Being forced to live in unheated and filthy rail cars and with inadequate food, Kruger was one of several guards who fell ill in October 1918. He died October 21, 1918 of pneumonia after contracting Spanish flu, aged 21. Two other guards died of the same condition. (See https://onthewarmemorialtrail.com/2018/10/25/the-forgotten-ww1-soldier/)

- WWI soldier Leigh Hunt CAMERON of Albany was serving with the 105th Battalion, C Company, when he caught measles and developed pneumonia, and passed away at the Military Hospital in Charlottetown on May 5, 1916, one day before his 18th birthday. (See https://onthewarmemorialtrail.com/2019/04/29/the-ww1-soldiers-who-never-left-canada/ and https://onthewarmemorialtrail.com/2021/03/24/the-search-for-a-photo-of-leigh-hunt-cameron-moves-to-youtube/)

Andrew MacKay (left), Pieter Valkenburg (centre) and Jim Glennie (right) at the grave of Leigh Hunt Cameron. (Photo credit: Daria Valkenburg)

….The 6 step process of inspecting and cleaning a grave…

The first grave Pieter inspected and cleaned at the Cape Traverse Community Cemetery was that of Elmyr Kruger…..

Step 1 – Take a photo of Elmyr’s grave before cleaning begins. (Photo credit: Daria Valkenburg)

Step 2 – Take a photo of the graves that are around Elmyr’s grave. (Photo credit: Daria Valkenburg)

Step 3 – Gently brush off dirt on Elmyr’s grave. (Photo credit: Daria Valkenburg)

Step 4 – Wash Elmyr’s grave with water. (Photo credit: Daria Valkenburg)

Step 5 – Gently brush dirt off of the sides and back of Elmyr’s grave. (Photo credit: Daria Valkenburg)

Step 6 – Wash the sides and back of Elmyr’s grave with water. (Photo credit: Daria Valkenburg)

….Over 100 years old but a very clean grave now…

Rev Kent Compton and Pieter by the WWI grave of Elmyr Kruger. (Photo credit: Daria Valkenburg)

The grave of Elmyr Kruger has been in place in the cemetery since October 1918, and now looks almost like new after being cleaned! Rev Compton and Pieter visited Elmyr’s grave a few days after it was cleaned.

….Can you help with finding photos?…

While a photo of Harold ‘Lloyd’ Lefurgey was provided by family years ago, no photo has yet been found for Elmyr Kruger or Leigh Hunt Cameron. If you can help with finding a photo, please email Pieter at memorialtrail@gmail.com or comment on the blog.

When asked about his new role as a CWGC volunteer, Pieter had a simple reply. “…It’s an honour for me to take care of those graves, which I’ve already visited several times as a member of the Borden-Carleton Legion Branch, when we place flags at the graves of veterans during Remembrance Week…” (See https://onthewarmemorialtrail.com/2024/11/03/on-the-war-memorial-trail-borden-carleton-legion-honours-veterans-by-placing-flags-at-their-graves/)

© Daria Valkenburg

….Want to follow our research?…

If you are reading this posting, but aren’t following our research, you are welcome to do so. Our blog address: https://onthewarmemorialtrail.com/

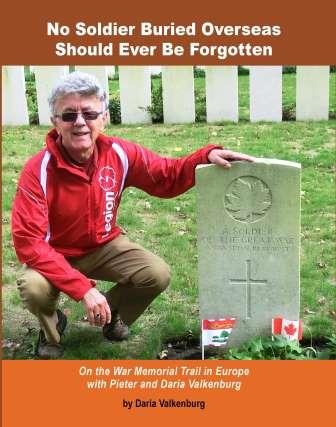

4 countries, 6 weeks, 7,000 km – an unforgettable war memorial journey in Europe…. Daria’s book ‘No Soldier Buried Overseas Should Ever Be Forgotten‘ is available in print and e-book formats. Net proceeds of book sales help support research costs and the cost of maintaining this blog. For more information see https://nosoldierforgotten.com/

4 countries, 6 weeks, 7,000 km – an unforgettable war memorial journey in Europe…. Daria’s book ‘No Soldier Buried Overseas Should Ever Be Forgotten‘ is available in print and e-book formats. Net proceeds of book sales help support research costs and the cost of maintaining this blog. For more information see https://nosoldierforgotten.com/

Subscribe to our YouTube Channel: On The War Memorial Trail With Pieter Valkenburg: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCJ591TyjSheOR-Cb_Gs_5Kw.

Never miss a posting! Subscribe below to have each new story from the war memorial trail delivered to your inbox.