February 8, 2020. Recently, Pieter and a friend went to see the British WW1 movie ‘1917’, which is nominated for several Oscars and has a Canadian connection due to a map used in the film. (For that story see https://www.cbc.ca/news/entertainment/1917-canadian-contribution-1.5450608) The story takes place in France on April 6, 1917, and is about two men tasked with delivering a message to another unit to warn of a German ambush. The men go through several towns and villages in France’s Western Front. Canadians may remember this period as being the lead up to the Battle of Vimy Ridge on April 9, 1917.

Pieter found the movie of great interest for several reasons. It was a depiction of the horrors of war… without being overly gory. After being through the trenches and tunnels in Vimy Ridge a few years ago, he was intrigued to see the way soldiers sat on either side of a trench while waiting to go up into battle. But the main reason he liked the movie is that it told the story of two people.

Contrary to what we learn in history books and classes, in the end all history is the cumulative stories of individuals. A list of names on a cenotaph, such as the one outside the Borden-Carleton Legion, is meaningless without knowing who those people were and what happened to them. This is what started Pieter on the journey to uncover the stories behind the names on the Cenotaph.

Over the years, the stories of those from WWI have been told in this blog. 24 are listed on the Cenotaph and half of them died in France…. Patrick Raymond ARSENAULT and John Lymon ‘Ly’ WOOD are listed on the Vimy Memorial as their bodies were never identified. Also killed in France were Kenneth John Martin BELL, James CAIRNS, James Ambrose CAIRNS, Arthur Leigh COLLETT, Bazil CORMIER, Patrick Phillip DEEGAN (DEIGHAN), Joseph Arthur DESROCHES, Percy Earl FARROW (FARRAR), Ellis Moyse HOOPER, and Charles W. LOWTHER. We were at the Vimy Memorial and visited each grave.

Five men died in Belgium. Two are listed on the Menin Gate Memorial in Ypres, as their bodies were never identified: Charles Benjamin Murray BUXTON and George Albert CAMPBELL. We visited Menin Gate and the area where they died. We also visited the graves of James Lymon CAMERON, Vincent Earl CARR, and Arthur Clinton ROBINSON.

Vincent Carr, who died during the Battle of Passchendaele on October 30, 1918, was initially buried in a trench with 4 others – two Canadian and two British soldiers. Decades later, when they were reburied in a Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemetery, all three Canadians were still identifiable. The British Army’s cardboard identity ‘tags’ had disintegrated, leaving the two British soldiers as unidentified. Today, DNA testing can be done to help with identity, but decades ago this was impossible.

Two men died in England. John Goodwill HOWATT was wounded in France, and died in a British hospital. Bruce Sutherland McKAY had gotten ill during the transport from Canada to England and also died in a British hospital.

Henry Warburton STEWART survived the war, only to fall ill while in Germany as part of the occupation forces. He’s buried in a German cemetery in Cologne, which we visited.

James Graham FARROW (FARRAR) was not a soldier, but in the Merchant Navy, transporting vital supplies between England and France, when his ship was torpedoed by a U-boat.

Three men died on Canadian soil. Leigh Hunt CAMERON died of illness, while Harry ROBINSON died from blood poisoning. William Galen CAMPBELL was poisoned with mustard gas on May 28, 1918, a few months before the end of the war, but was able to return home. And yes, we’ve visited those graves as well.

We were also able to tell you parallel stories, such as that of Clifford Almon WELLS, who had many of the same experiences as John Lymon Wood, and also died in France. Another story was that of George BRUCKER, of the German Army, who was taken prisoner during the Battle of Vimy Ridge, and survived the war, never forgetting the two ‘tall’ Canadians who didn’t shoot him. Decades later his son, now in his 80s, is still hoping to thank the families of those two unknown men.

Thanks to Pieter’s curiosity in trying to find out why one Commonwealth War Graves Commission gravestone in a cemetery in Cape Traverse was not recorded on the Cenotaph, we were able to tell you the story of Elmyr KRUGER, a soldier from Saskatchewan who died of illness while guarding German prisoners of war from a POW camp in Amherst.

We’ve told the stories of each man, and shared our visits to the various cemeteries and war memorials. As photos and letters came in, we shared those experiences as well.

We are still missing photos of several of these soldiers, so the quest to put a face to every name and story is still ongoing. Who are we missing? Take a look and see if you can help:

UPDATE: Photos of James Cairns, Joseph Arthur Desroches, and Harry Robinson have been found!

It’s great to watch a movie about fictional characters, but let’s not forget the stories of real life people! There won’t be any Academy Awards given out, but they will be remembered. Research continues to uncover more stories. If you have a story or photo to share about any of the names mentioned in this posting, please contact Pieter at memorialtrail@gmail.com or comment on the blog.

© Daria Valkenburg

....Want to follow our research?…

If you are reading this posting, but aren’t following our research, you are welcome to do so. Our blog address: https://onthewarmemorialtrail.com/

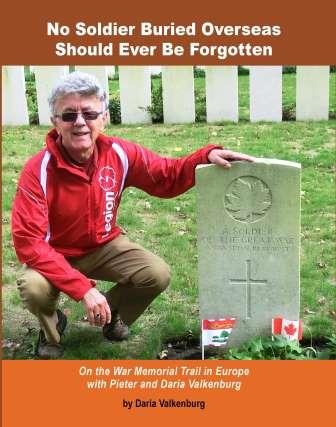

4 countries, 6 weeks, 7,000 km – an unforgettable war memorial journey in Europe…. Daria’s book ‘No Soldier Buried Overseas Should Ever Be Forgotten‘ is available in print and e-book formats. Net proceeds of book sales help support research costs and the cost of maintaining this blog. For more information see https://nosoldierforgotten.com/

4 countries, 6 weeks, 7,000 km – an unforgettable war memorial journey in Europe…. Daria’s book ‘No Soldier Buried Overseas Should Ever Be Forgotten‘ is available in print and e-book formats. Net proceeds of book sales help support research costs and the cost of maintaining this blog. For more information see https://nosoldierforgotten.com/

Subscribe to our YouTube Channel: On The War Memorial Trail With Pieter Valkenburg: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCJ591TyjSheOR-Cb_Gs_5Kw.

Never miss a posting! Subscribe below to have each new story from the war memorial trail delivered to your inbox.